Tah-Ro-Hon, An Ioway Warrior: Original Hand-colored McKenney & Hall Lithograph

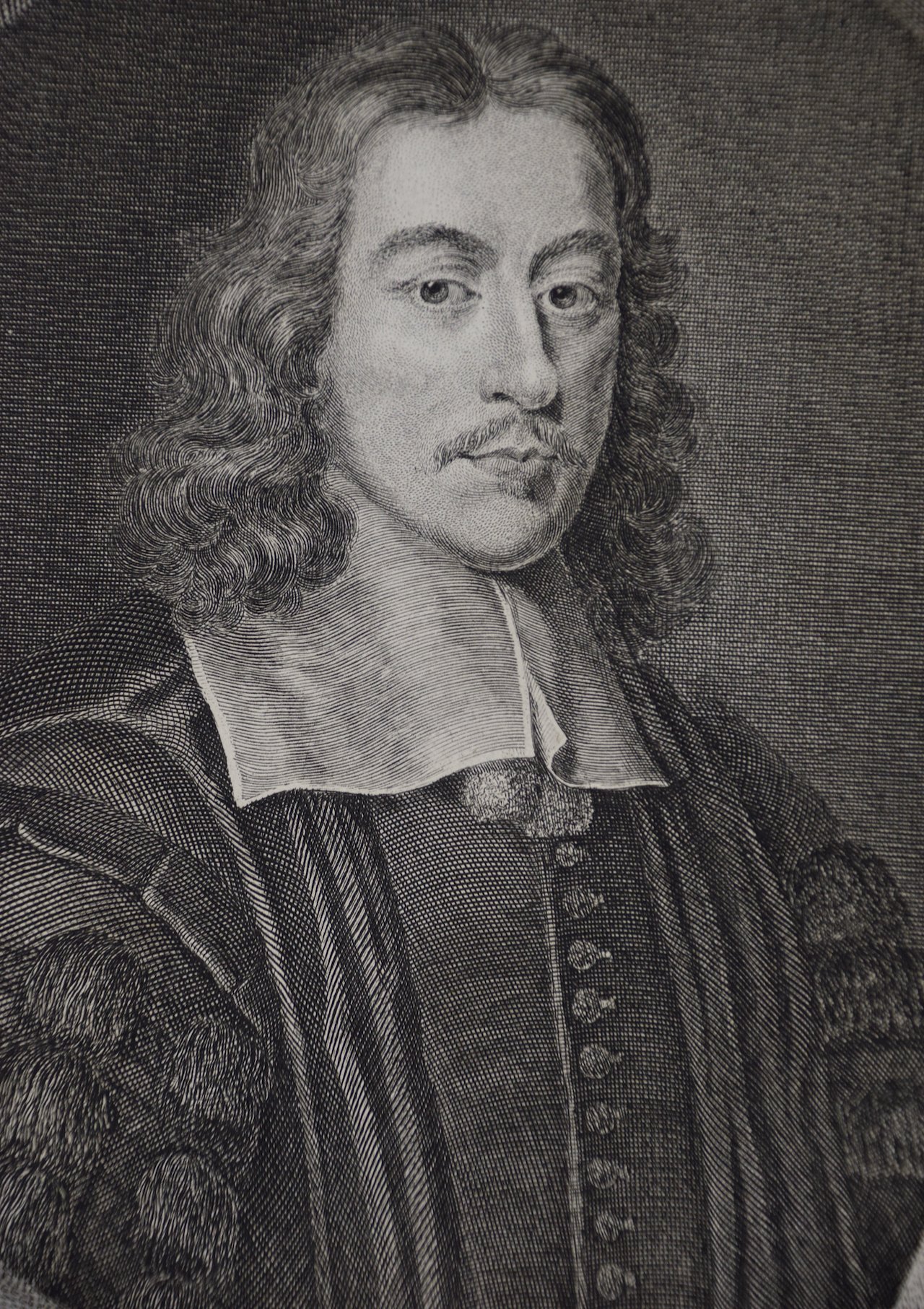

This is an original 19th century hand-colored McKenney and Hall lithograph of a Native American entitled "Tah-Ro-Hon, An Ioway Warrior", lithographed by J. T. Bowen after a painting by Charles Bird King and published by Rice and Hart & Co. in Philadelphia in 1848. For his portrait Tah-Ro-Hon is wearing a feathered multicolored headdress, long ornamental earrings, a chain necklace, a presidential piece medal on a ribbon necklace and he holds a multicolored staff with feathers.

Creator: McKenney & Hall

Creation Year: 1848

Dimensions: Height: 10 in (25.4 cm)

Width: 7 in (17.78 cm)

Medium: Lithograph

Condition: See description below.

Reference #: 4978

This is an original 19th century hand-colored McKenney and Hall lithograph of a Native American entitled "Tah-Ro-Hon, An Ioway Warrior", lithographed by J. T. Bowen after a painting by Charles Bird King and published by Rice and Hart & Co. in Philadelphia in 1848. For his portrait Tah-Ro-Hon is wearing a feathered multicolored headdress, long ornamental earrings, a chain necklace, a presidential piece medal on a ribbon necklace and he holds a multicolored staff with feathers.

Creator: McKenney & Hall

Creation Year: 1848

Dimensions: Height: 10 in (25.4 cm)

Width: 7 in (17.78 cm)

Medium: Lithograph

Condition: See description below.

Reference #: 4978

This is an original 19th century hand-colored McKenney and Hall lithograph of a Native American entitled "Tah-Ro-Hon, An Ioway Warrior", lithographed by J. T. Bowen after a painting by Charles Bird King and published by Rice and Hart & Co. in Philadelphia in 1848. For his portrait Tah-Ro-Hon is wearing a feathered multicolored headdress, long ornamental earrings, a chain necklace, a presidential piece medal on a ribbon necklace and he holds a multicolored staff with feathers.

Creator: McKenney & Hall

Creation Year: 1848

Dimensions: Height: 10 in (25.4 cm)

Width: 7 in (17.78 cm)

Medium: Lithograph

Condition: See description below.

Reference #: 4978

This original McKenney and Hall hand-colored lithograph is printed on a sheet measuring 10" high and 7" wide. There is a tiny spot of red paint adjacent to a red feather hanging from Tah-Ro-Hon's staff that occurred when the lithograph was hand-colored and a tiny, barely visible spot on the left. The print is otherwise in excellent condition. The original descriptive text pages, 173-177, from McKenney and Hall's 19th century publication are included.

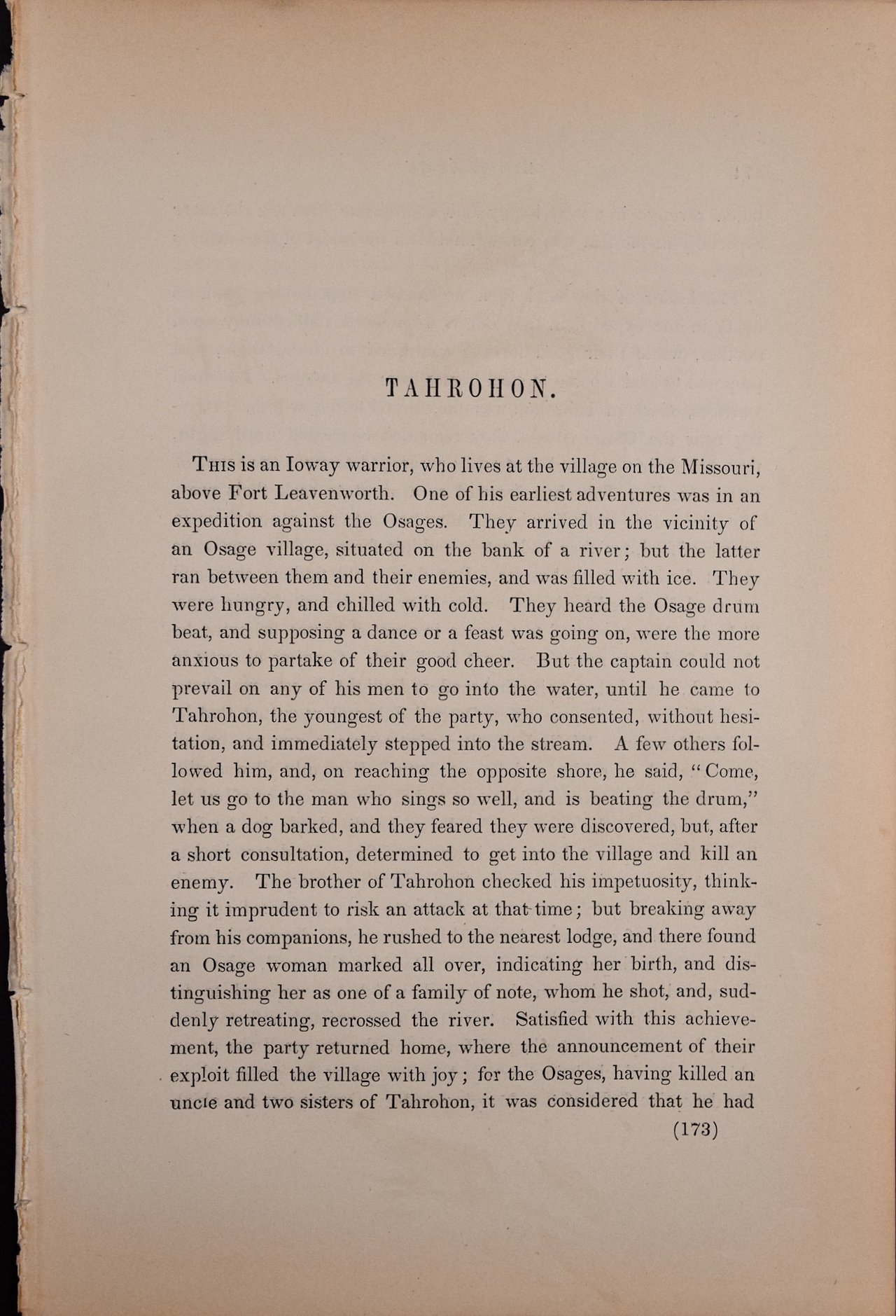

This is Tah-Ro-Hon's bio in McKenney and Hall's publication: "This is an Ioway warrior, who lives at the village on the Missouri, above Fort Leavenworth. One of his earliest adventures was in an expedition against the Osages. They arrived in the vicinity of an Osage village, situated on the bank of a river; but the latter ran between them and their enemies, and was filled with ice. They were hungry, and chilled with cold. They heard the Osage drum beat, and supposing a dance or a feast was going on, were the more anxious to partake of their good cheer. But the captain could not prevail on any of his men to go into the water, until he came to Tahrohon, the youngest of the party, who consented, without hesitation, and immediately stepped into the stream. A few others followed him, and, on reaching the opposite shore, he said, “Come, let us go to the man who sings so well, and is beating the drum,” when a dog barked, and they feared they were discovered, but, after a short consultation, determined to get into the village and kill an enemy. The brother of Tahrohon checked his impetuosity, thinking it imprudent to risk an attack at that time; but breaking away from his companions, he rushed to the nearest lodge, and there found an Osage woman marked all over, indicating her birth, and distinguishing her as one of a family of note, whom he shot, and, suddenly retreating, recrossed the river. Satisfied with this achievement, the party returned home, where the announcement of their exploit filled the village with joy; for the Osages, having killed an uncle and two sisters of Tahrohon, it was considered that he had taken revenge in a very happy and appropriate manner, the more especially as the feat was consummated in the midst of the enemy’s camp.

The leader of the band then proclaimed that, having been so lucky in one expedition, they ought to proceed immediately upon another, while their good fortune continued to attend them, and proposed to lead a party to steal horses from the Osages. Fourteen warriors, of whom Tahrohon was one, agreed to follow him. Arriving near the Osage village, they remained concealed until night, then hid their guns, and cautiously proceeded towards the scene of action, sending Tahrohon forward as a scout, to seek their prey. Not succeeding in finding horses, they began to cast round them in search of food, for they had eaten nothing for two days, and were almost famished with hunger. But they could find no corn, and returned dispirited to the spot where they had deposited their guns. Tahrohon then proposed to go again in quest of horses, believing he should find some near a creek not far distant. Groping his way in the dark, with that sagacity that renders daylight almost superfluous to the Indian, he discovered an Osage lodge, and regretted that he had left his gun. While hesitating what course to pursue, the tall grass rustled near him, and he sat down. Presently all was still. He cautiously approached the camp, and discovered a piece of buffalo meat hanging at the opening of a lodge, barely visible in the dim light thrown upon it by an expiring camp fire. He determined to steal it, but remained for some time wistfully gazing at the spoil, and endeavoring to measure the danger to be encountered against the chances of success. Approaching nearer by degrees, he was at length in the act of reaching up to seize the spoil, when he discovered something on the ground, which he supposed to be two sacks of corn, a prize too tempting to be resisted, and stooping down he grasped not a bag of food but the nether limbs of an old woman, which, being wrapped in large leggings, presented, in the deceptive light of the decaying embers, the appearance which deceived the hungry prowler. When his hand rested on a human being, he sprang back terrified, and was about to run off, when he reflected that if he turned his back he would probably be shot by the warriors occupying the camp; and, drawing his knife, he boldly stepped forward to meet the danger, and slay the first who should oppose him. It turned out that the encampment comprised but one lodge, the sole occupant of which was an old squaw.

As this party returned home they discovered a trail, such as is made by dragging over the grass the kind of sled on which the Indians carry off their wounded. As the track led towards their village, they followed it, and overtook a party of their own people, headed by Wahumppe, who had had a fight with the Osages and Kansas. Though surprised and surrounded by superior numbers, but one of the Ioway was killed. Hard Heart was wounded three times, and it was he who was drawn on the sled. Ten days after, another war party went out to revenge the death just mentioned; for thus in savage life one deed of violence leads to another; and whether we pursue the annals of a tribe, or the biography of an individual, the tale is but a series of assaults and reprisals. But although the Osages were the offending party in this instance, it was determined to wreak their vengeance upon the Sioux, probably because the latter were most likely to be unprepared for such a visit, When they reached the Sioux country, spies were sent out, The leader made a talk to his warriors, and concluded by inviting them to tell their dreams, upon which two individuals said they had dreamed that they had gone through a great country, and had seen many people, but no one molested them. This was considered a good dream. Presently the spies came in, and reported that they had discovered fifteen lodges of the Sioux. This intelligence made them cautious, and they concealed themselves for twenty-four hours to consult and feel their way. Then the horses were hobbled, a guard put over them, and the main body marched to the attack. To avoid being discovered, as well as to prevent any one from straying off and being taken for an enemy, they moved in a close body, each man touching his fellow. The constraint imposed by this unusual movement displeased Tahrohon, who determined, by a trick, to anticipate his companions, and strike the first blow. Accordingly he stepped aside from the main body, and threw himself on the ground, pulling down with him an Indian, who was his relative, and who, like himself, had been displeased by some neglect. These two, determining to seek honor in their own way, remained still until the war party passed, and then rushed into the village of the enemy, by the point at which it was supposed the inhabitants, when alarmed, would attempt to retreat. But the spies, with the true Indian craft, after communicating the truth to the leader of the band, had spread a false report among his followers, and our adventurers entered a deserted place, while the enemy was flying in an opposite direction. Thus disappointed, and placed in an equivocal position, they determined to return home, and to frame some plausible excuse for their desertion. They had not traveled far when they came suddenly on a Sioux camp, composed of several skin lodges that were new and white, and upon which the moon was shining clearly. Here was a chance to do something. ” Let us take a smoke,” said one to the other; and sitting down among the tall grass, they lighted a pipe, and began to consider what act of mischief might be perpetrated upon the sleeping inmates by two desperate marauders, bent on distinguishing themselves at any hazard. After smoking and peeping awhile, they found a horse; and their spirits being raised by this success, they groped about actively and soon discovered four more, which they led to a grove in a bend of the river, where they hid them, for they were not satisfied with what they had done. But before they could re turn to the lodges, day dawned, and a prophet was heard singing, shaking his gourd, and praying for the relief of a sick person. A Sioux Indian came to the river for water, and our hero stepped for ward to kill him, but just as he was about to fire, his companion ex-claimed, “Look, there is our army!” The young men stood for a moment stupefied with surprise and terror; for the danger now was that the Ioway band, rushing forward upon the Sioux lodges with loud yells, would not recognize these youths found thus in the enemy’s camp; nor was it likely they could make themselves known in the noise and smoke of the onset. They sprang, therefore, down the bank of the river, and attracted the attention of the prophet, who called on his people, who had not yet discovered the advancing Ioway, to fire on them. But at that instant the Ioway raised the war-whoop, and rushed forward. The two young men, in danger from both sides, attempted to mingle in the fight, but found the missiles of both parties hurled at them. At length our hero, seeing the two Sioux surrounded by several Ioway, who were pushing each other aside in their eagerness to strike a foe, rushed through the circle and shot one of the Sioux. He then mingled in the fight, and felt like one relieved from the horrors of a disagreeable dream, when he found himself fairly reinstated among his friends. In this fight twelve Sioux were killed, and four were taken prisoners."

Col. Thomas J. McKenney was Superintendant of The Bureau of Indian Affairs from 1816 until 1830. He was one of a very few government officials to defend American Indian interests and attempt to preserve their culture. He travelled to Indian lands meeting the Native American leaders. He brought with him an accomplished artist, James Otto Lewis, who sketched those willing to participate. A large number of the most influential Indian chiefs and warriors were later invited to come to Washington in 1821 to meet President Monroe. McKenney commissioned the prominent portrait painter Charles Bird King, who had a studio in the capital, to paint these native American leaders, who chose the costumes they wished to wear for the sitting. The magnificent resultant paintings were displayed in the War Department until 1858, and were then moved to the Smithsonian Institute. When Andrew Jackson dismissed McKenney in 1830, he gave him permission to have the King portraits as well as some by other artists, including George Catlin and James Otto Lewis, copied and made into lithographs, in both folio and octavo sizes. McKenney partnered with James C. Hall, a Cincinnati judge and novelist to publish the lithographs and the text written by Hall. The work was extremely expensive to create and nearly bankrupted McKenney, as well as the two printing firms who invested in its publication. The resultant work gained importance when Catlin's paintings were destroyed in a warehouse fire and Charles Bird King's and James Otto Lewis’ portraits were destroyed in the great Smithsonian Museum fire of 1865. The McKenney and Hall portraits remain the most complete and colorful record of these pre-Civil War Native American leaders.

The folio and smaller octavo sized hand painted lithographs remain prized by collectors and institutions, many of which are held by major museums and collections, including the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian Institute.